The Dungeon Game

My son is 5 this April. Like most kids he loves games, particularly any that involve a high level of freedom along with a generous helping of pretend violence. Unsurprisingly, I've encouraged him to express his interests through the classic dungeon crawl, built from simple rules borrowed from indie RPGs. Together we build a dungeon, assemble a party, and fight monsters. Sometimes we give the monsters jelly beans. At the end we share in the spoils (for some reason, this was super important to my kid). If you want to jump to the rules, skip ahead.

What is a game?

Ha, what a title! OK so here's the deal: a game is a kind of play that has semi-consistent rules. Easy, and no one is left out. That said...

What makes a game interesting?

I'm afraid I've become a bit of a snob the past few years, especially when it comes to games designed for children. My son has been making up games since he was two years old and playing roleplaying and board games since he was three. He isn't special in this regard, either: play is something for which children seem to need no instruction. Many of his friends play games above the recommended age indicated by the box; the only distinction in capability appears to be familiarity with the core concepts (e.g. how many games they've previously played)

It seems like the board games boast that they help teach children important lessons through play, including cooperation, critical thinking, patience, etc. Although these sorts of games tend to teach the basics pretty well (taking turns, numbers mean things, etc) they rarely foster fun, long-term play. Frequently, these kinds of games fail to consider one thing that children (and adults) really do care about: Agency. What makes a game interesting (and fun) is the level of decision-making agency a player has each turn, and most children's games seem to have forgotten this.

In many games the results of play are pre-determined: in Candyland, the game session has already been written once the cards are shuffled. In Count Your Chickens, a spinner is used to determine the next move, and the next, and so on. There is no input from the players; a robot arm could shuffle the deck or flick the spinner and the results would unfold exactly the same way. There is no strategy, logic, or decision-making on the part of the player.

This does not mean that these games have no value; Candyland is a great structure for learning the basics: turns, pieces, cards, etc. It has a fine history as well. But the basic structure has been repeated in other games, sometimes with simple changes (dice for cards, apples for candy). I feel like children eventually tire of these sorts of games, moving toward mixed systems like Sorry!, and (hopefully) later on towards play experiences built around skill, player choice, and imagination.

I am fortunate that my child quickly moved on from the agency-free games and into competitive and cooperative games of skill and chance. If you're curious, here are a few that we like:

- Amazing Tales

- Hoot Owl Hoot

- Sequence (for kids)

- Sorry!

- Race to the Treasure

- Rivers, Roads, Rails

- Outfoxed!

- Parcheesi

The Dungeon Game

Edit: You can now download this game as a PDF or Booklet.

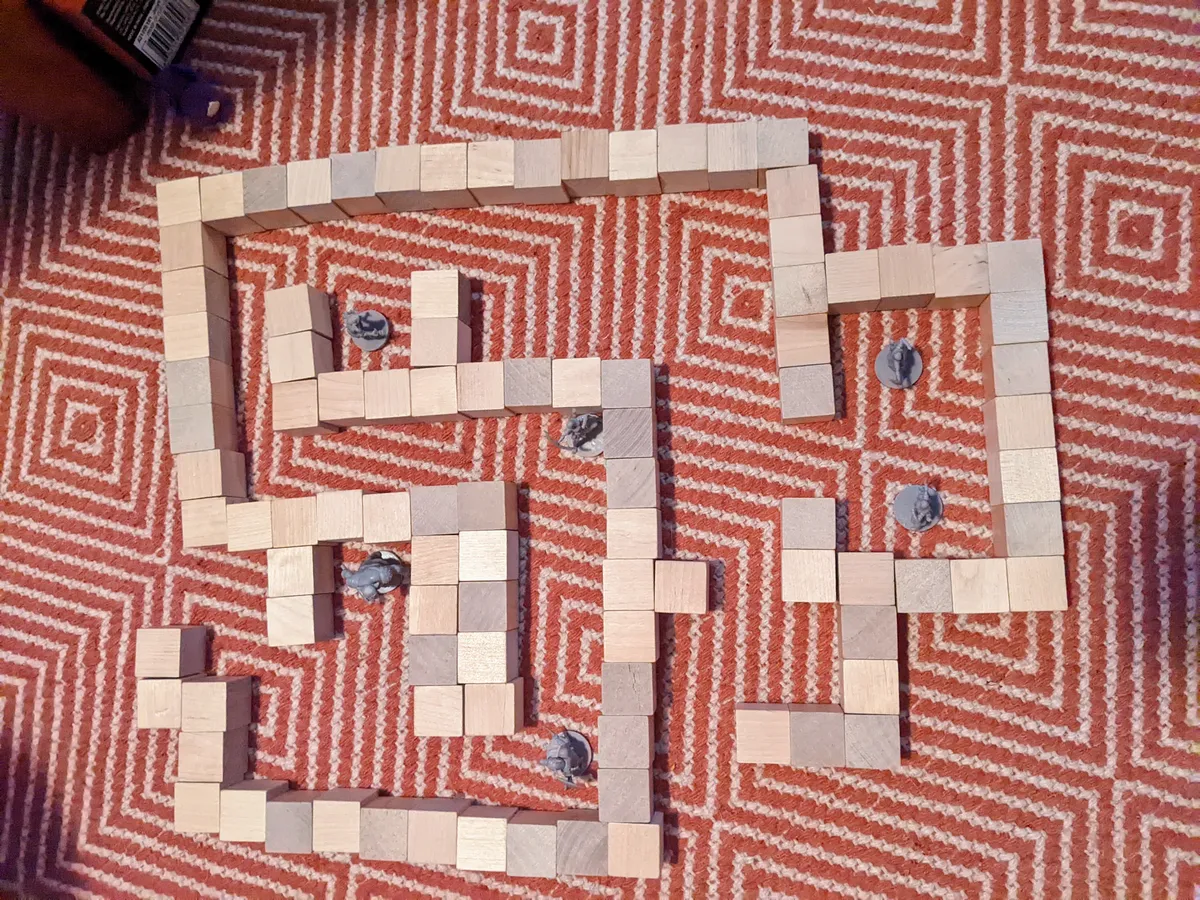

My son and I wrote this game together. It's pretty simple, uses minis/game pieces and wooden blocks and can be played with or without a GM. Adventurers explore a dungeon or cool location, searching for treasure and fighting monsters. I don't really like "suggested ages" or whatever, but 3 and up seems like a solid range.

Like everything I write, this game is released under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

Setup

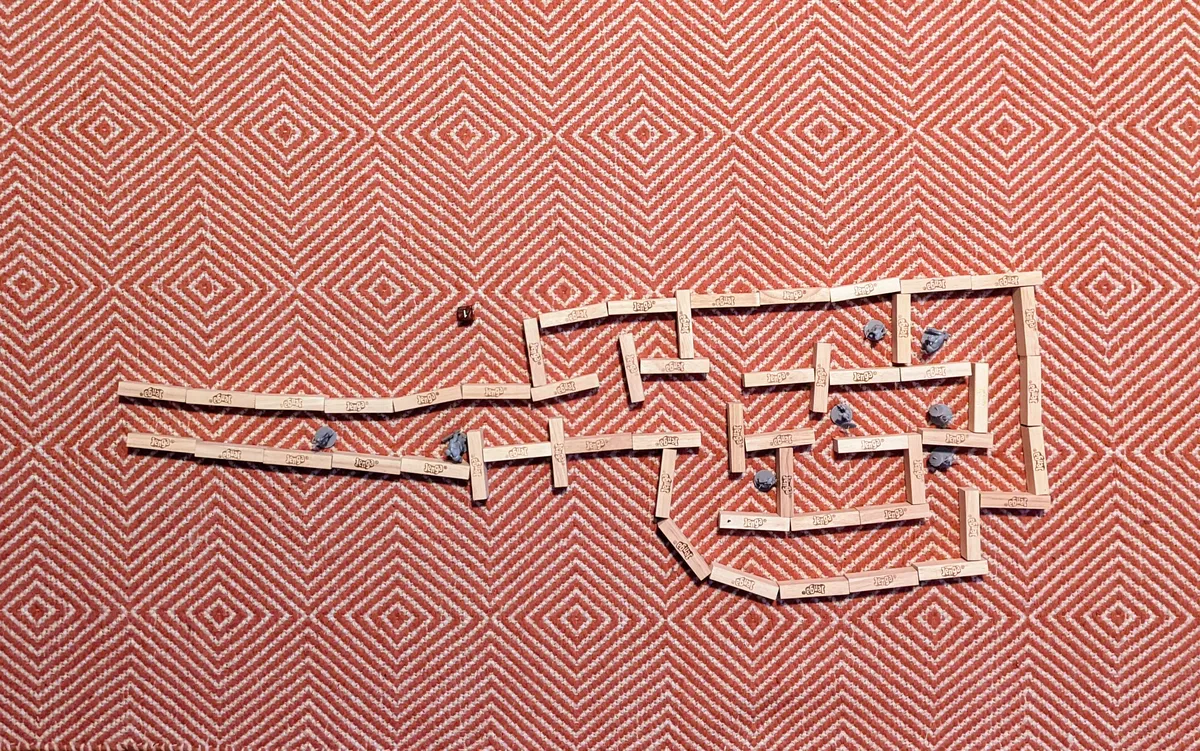

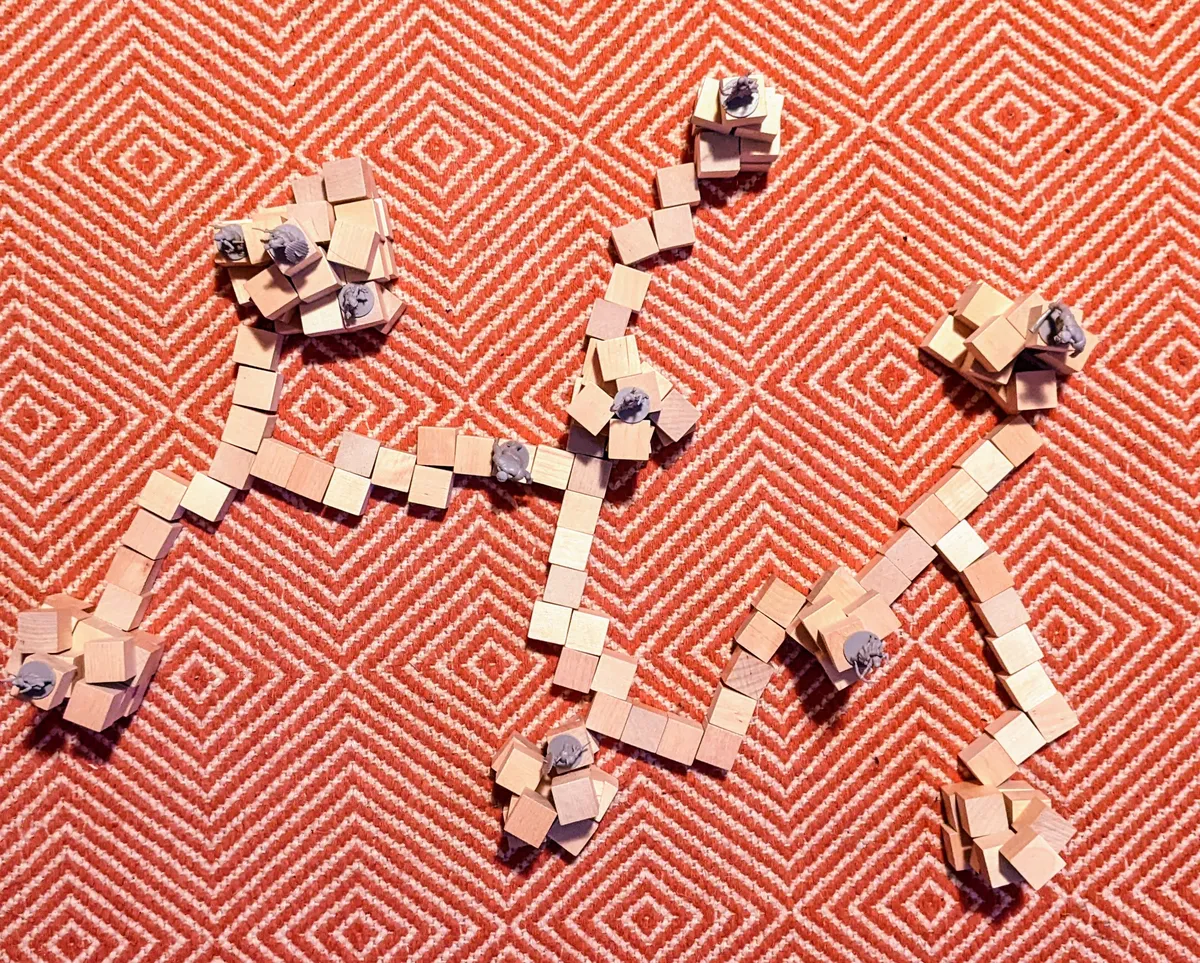

- You will need at least one d6 to play, as well as wooden or plastic blocks of any kind.

- Together, build a dungeon, forest, town, canyon, etc. Improvise!

- Populate your play setting with monster, traps and treasure. Miniatures are obviously a great choice, but pieces from other board games work well too.

- Most importantly, get some real treasure. Licorice, fruit, chocolate coins, whatever. Put it to one side, with instructions that it not be touched until the adventure is concluded.

- Finally, come up with a reason for the Adventurers to explore the dungeon. Some examples:

- To find treasure (gold, items & scrolls)

- To rescue a kidnapped friend or important person

- To explore a new place

- To rid a locale of some dangerous foe

Basic Rules

- Creatures have a Defense (a combination of health and armor), as well as an ability or weapon bonus, but no other stats.

- On their turn, an Adventurer can move and take an action or attack.

- When a creature takes a risky action, roll a d6. A roll of a 5-6 is a success.

- Add a maximum of +1 to the roll if the creature has an item or skill that can help them succeed.

- Any action is possible at any time. The fancier the action, the greater the consequences of failure. Make a determination as a group whether a +1 should be added to a roll.

Optional Rule: If you want the game to be easier or faster change the result to a 4-6. This applies to both combat and risky actions.

Combat

- Initiative: At the start of combat both sides roll a d6, the higher goes first.

- Each side takes turns. Adventurers and monsters go in whatever order they wish.

- Attackers roll a d6; on a 5-6 they are successful. Some weapons or abilities provide a +1 bonus to the attack.

- Normal attacks do 1 damage unless otherwise indicated.

- Healing: Adventurers can return to a place of safety and wait a turn to make a healing roll. On a 5-6 they regain 1 Defense. Monsters may catch up during this time!

Magic

- Spells can be found in spellbooks and can be cast once per adventure.

- Casting a spell takes an action and does not require a roll to succeed.

- Using a spell beyond its basic use (e.g. Levitate multiple targets) may require a roll.

- Scrolls are single-use spells not typically found in spellbooks.

Common Spells

- Beast Form: Turn into any wild creature until you take damage.

- Cure Wounds: Target recovers 1d6 Defense.

- Elemental Mastery: Control water, fire, earth, air.

- Fireball: Ball of flame that targets multiple creatures.

- Fog Cloud: A white vapor obscures your movements.

- Fortify: A target gets 2 extra Defense.

- Freeze: Turns a target to ice. Very effective on liquid surfaces.

- Illusion: An illusion of the caster's choice appears within eyesight.

- Levitate: Fly over any surface and as high as a tree.

- Lightning: 3 damage against metal armor.

- Magic Tongue: Speak any language.

- Message: Send a psychic message to an ally.

- Sleep: 1d6 creatures fall asleep.

Adventurers

- Knight: 8 Defense, Broad Sword (+1 to melee attacks), Shield, +1 to strength actions.

- Fighter: 6 Defense, Dual Swords (roll twice and keep highest), +1 to dodging actions.

- Ranger: 5 Defense, Bow (+1 to ranged attacks), 3 poison arrows (2 damage each), Short Sword, +1 to tracking actions.

- Thief: 4 Defense, Two Daggers (+1 when thrown), Backstab (2 damage to surprised targets), Lockpicks, +1 to thieving actions.

- Magic-User: 3 Defense, Staff, Spellbook (5 spells), +1 to magical actions.

All adventurers start with a rope, a torch, a bedroll, etc.

Monsters

- Assassin: 4 Defense, Poison Bow (+1 to ranged attacks), dagger.

- Bandit Leader: 3 Defense, Sword, Leadership (+1 to Initiative)

- Goblin: 1 Defense, Sword (+1 to attacks in groups of 3 or more).

- Lizardkin: 2 Defense, Sword & Shield, Roar (calls for aid).

- Ogre: 5 Defense, Club (hits 2 targets).

- Shadow Monster: Mimics any creature's Defense/abilities.

- Sorcerer: 3 Defense, Staff, Spellbook (2 spells).

Treasure

- Circlet of Seeing: Reveals invisible objects and creatures.

- Crystal Eyes: Goggles that allow for 360 degree view allowing the wearer to always go first.

- Globe of Water Walking: Allows you to walk on water until you take damage.

- Guiding Charm: +1 to ranged attacks, glows when danger is near.

- Magic Rope: A fifty-foot rope that follows your command.

- Pocket Dimension: Sucks objects and creatures into another plane.

- Pocket-Wall: A small tube of clay that spreads to cover any opening.

- Poison Dagger: 2 Damage to target on a roll of 6.

- Ring of the Beholder: The wearer's appearance matches whomever last wore the ring.